LLMs suck at variance.

LLMs seem pretty smart. They are acing the international math olympiad, making award-winning art humans, and ranking in the top ten in international coding competitions.[1]

Language models have really struggled at tasks where, given these achievements, you'd expect them to excel:

- Clicking around on a website (e.g. going through a checkout flow, using google sheets in the browser)[2]

- Creating simple, accurate deliverables for desk jobs (e.g. research reports, provisional patent applications)

- Playing games like chess (didn't we solve this already?) and Pokemon

They help humans do these tasks much faster, but can't do them end to end. The Computer Use model can't find the right button to click on the page, the Deep Research report has hallucinations and jumbled points, and GPT-5 plays illegal chess moves without realizing.

Why are these simple tasks so hard for models?

1. They are often performed without a large "harness," a set of custom tools that make the task easier.

Cursor is a harness for coding, giving LLMs a set of functions (grep, patch, vector search, web search) it can use to understand and edit code. If you want to help an LLM play chess better, a simple harness might involve giving it a list of legal moves to choose from.

Harnesses help LLMs excel: the stronger the harness, the easier the task becomes. Nobody has built a good harness for clicking around on a website yet.

2. They are often performed without a dedicated training effort.

The models got good at coding and math because engineers at OpenAI and Anthropic put plenty of good coding and math examples in the training data. No similar curation effort has taken place for most everyday digital tasks.

If the internet is main the training set for language models:

- They have seen 10 bad research reports for every good one. They have a hard time telling the difference.

- They have seen very few computer screens in their training, as the text from the pages was fed into them directly. They don't know how to click around on a website.

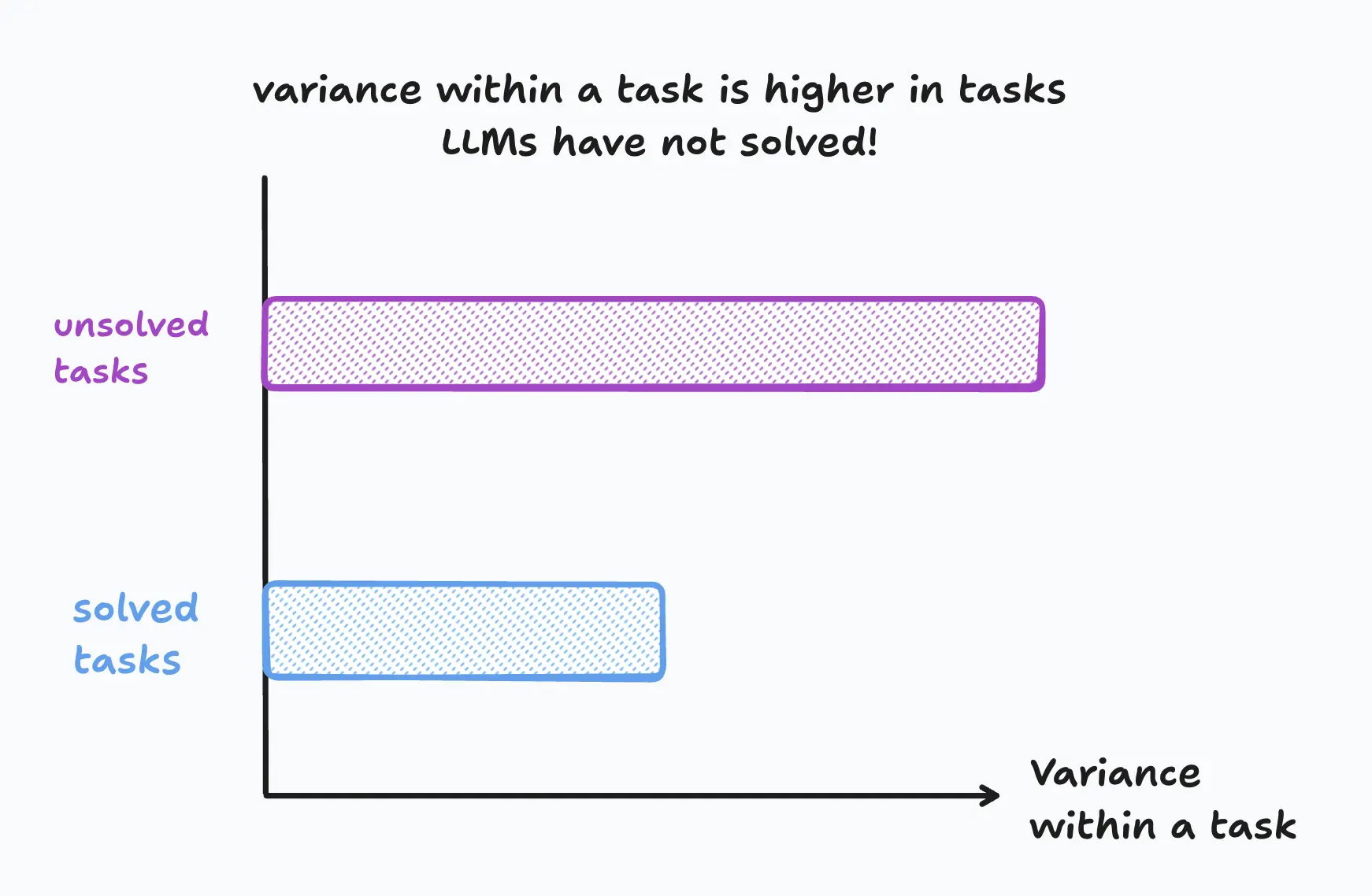

3. These tasks have high variance, meaning that to succeed at them often, you need to know a wide variety of details, tricks, and unwritten rules.

Each time you perform a "high variance" task like navigating a website checkout flow, it changes shape. Buying shoes on etsy.com is different from buying shoes on a website made in 2008.

Clicking on a website requires handling thousands of complexities (ignoring popups, clicking back and forth, knowing when to scroll, telling the difference between errors and slow loading) and has to work on any website. Navigating websites is easier than navigating a computer (a collection of websites, apps, folders, notifications). Navigating a computer is easier than performing tasks on one, because you have to navigate thousands of combinations of these computer windows and do the task.

We can always add better harnesses and training data, but we cannot escape the high variance in new tasks. In technical terms, high variance tasks will always have a high rate of out-of-distribution examples, even if your training set is very large.

Real-world tasks have high variance.

Competition math problems are not. Math is really, really hard, but you don't have to ask Dave for the Notion doc with reference material. You don't have to figure out whether the button is broken or you are just not clicking it right. If you learn more math and practice more math, you will solve more of the types of self-contained, but tricky problems you see in the international math olympiad.

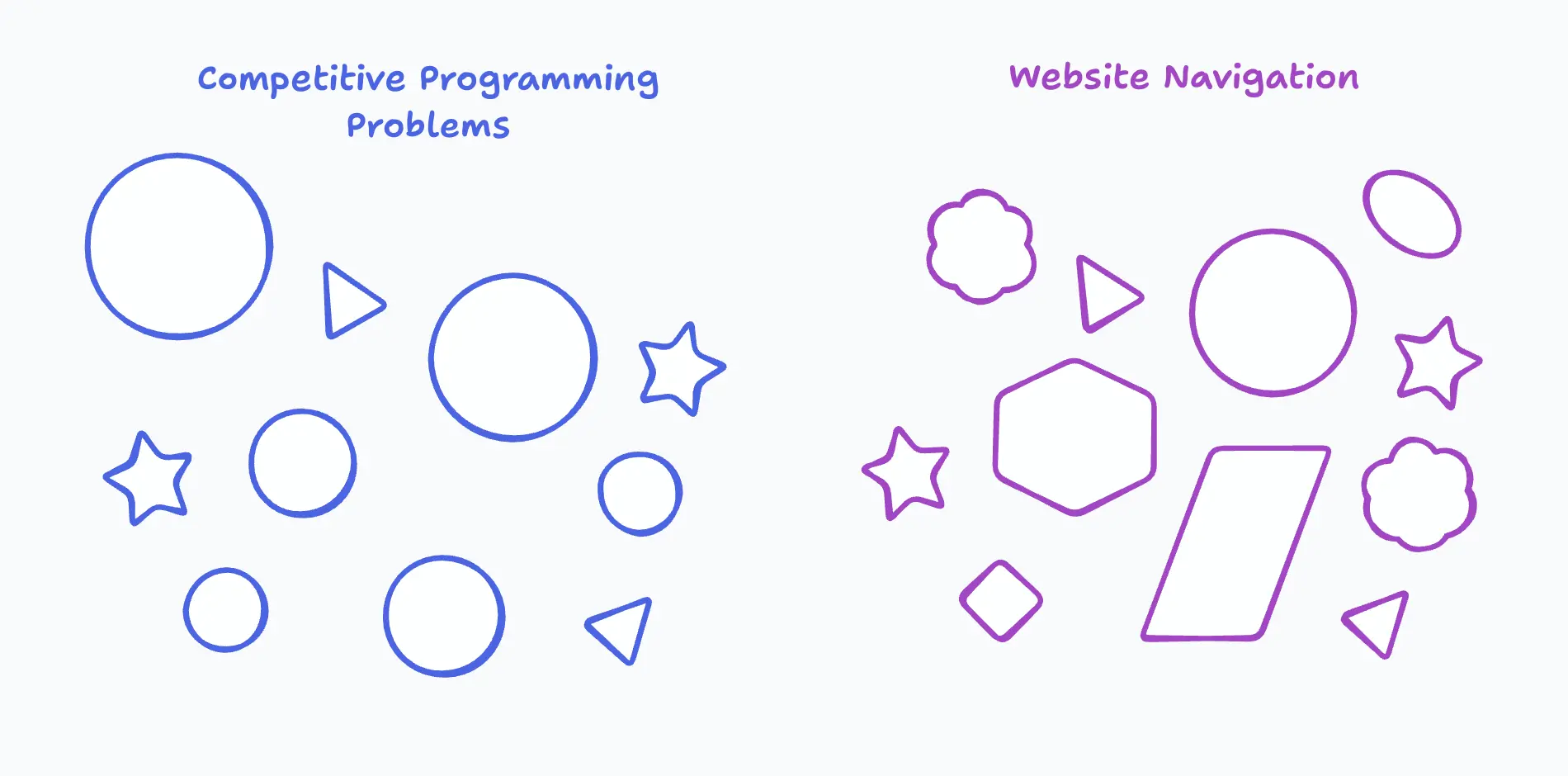

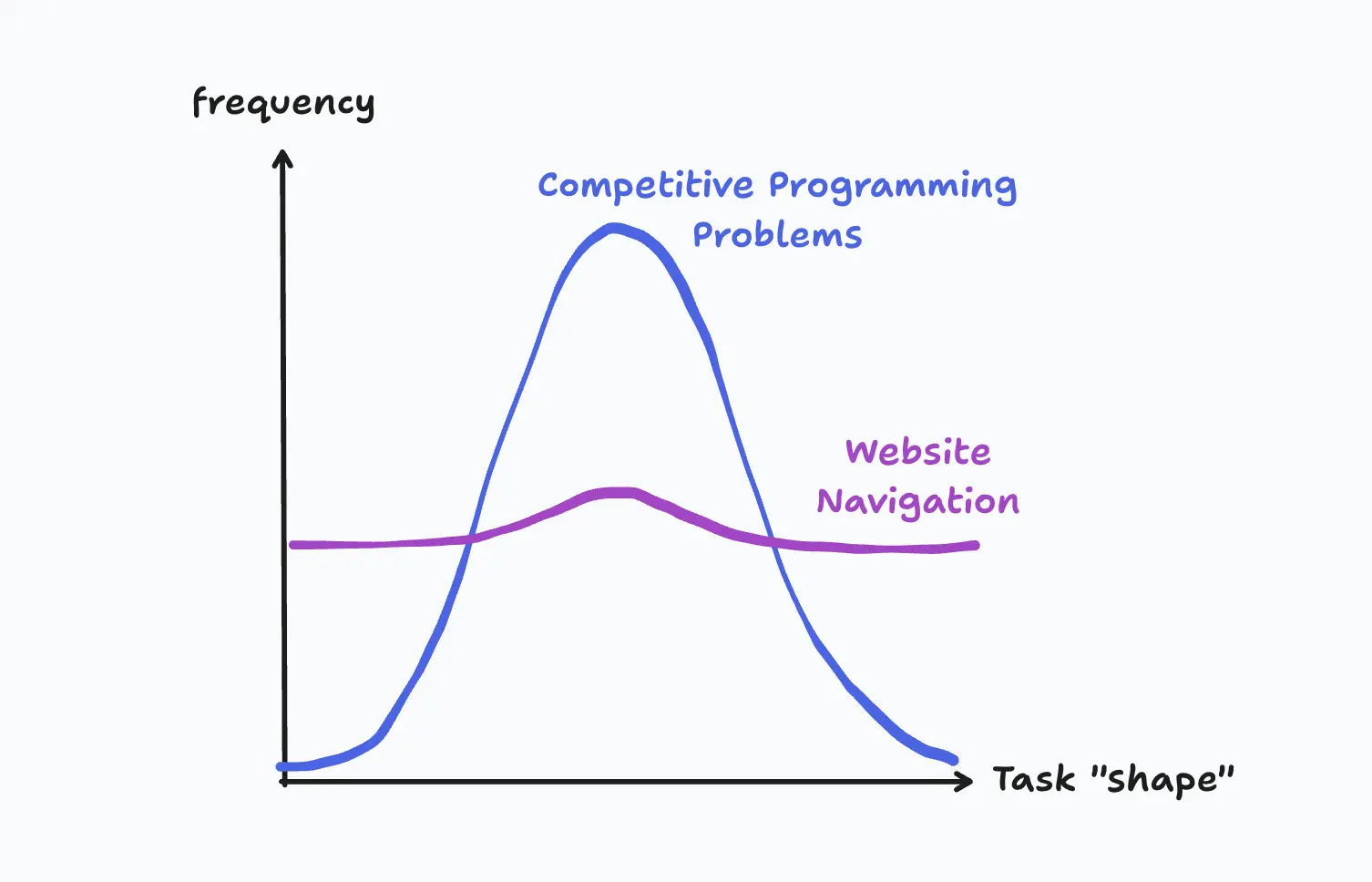

Competitive programming problems have common patterns across questions. There is much more variance between websites.

By solving the most common competitive programming problems, you solve the majority. In contrast, by solving the most common website navigation tasks, you solve navigation for a small fraction of websites.

This is a bit like the difference between sciences and the humanities in college. Physicists have to constantly learn new concepts and skills to progress; History majors have to learn new content, but the only skill they need is writing a good essay, which is their final assignment in every class.[4] Physicists have to leverage those new concepts to get the right answer: you must take a specific reasoning step in your proof to solve it. English majors could take 1,000 different, equally good approaches to an essay: each must be read cover-to-cover to understand its merit.

Real world tasks are messy. Even if you understand how to write a research report, you have to understand the content you are writing about, pull from dozens of information sources (some of which are easy to access, others are hidden internally in your company), ask questions, scrutinize poorly formatted data and sniff out errors, and write in the particular style your company requires.

To perform well, you cannot build a model that is a "good researcher" and a "good writer" because most of the tasks required to be successful are high variance. Success is highly contextual:

- For Company A, a report should be 5 pages, for Company B it should be 500.

- At Company C, only one person has been writing these reports for 20 years and they retired a month ago, so there is no documentation for best practice—as you look through their reports, you don't understand which parts are mistakes and which parts are the company's eccentric preferences.

- Company D has scattered documentation, which you have to traverse Slack, Google Doc comments, and of course the annual four week employee onboarding course, which is not recorded and won't run again until September.

- At Company E, people have all been working there for so long that they don't realize their specific requests are unintuitive, and don't help you when you're confused.

Each individual company has its own task variance. For them to implement an AI report-writer as more than a helpful starting point, they'll need to do the following:

- Gather and/or write documentation

- Identify unwritten rules they have been following, and write them down

- Gather a set of exemplar reports and write down why they are exemplar

- Put someone in charge of evaluating the model's performance and fleshing out documentation where needed

Evals are critical for high variance tasks, but they're tricky.

To check if a model got a competitive programming problem right, you check if model_answer == correct_answer. Done. To check if a report is good, you have to read it. For math problems, you can run thousands of training iterations until it gets the right answer. Since you need a human in the loop to read reports… running multiple iterations will be trickier.

There is a middle ground, where you write a rubric for your task, then have a "grader" model, another LLM, grade your model's performance, assigning a score from 0-1.

- For long form tasks, the grader won't be able to catch all of a model's mistakes. The model may have misinterpreted a source, or broken an unwritten rule that wasn't in the documentation, or taken a task in an internally coherent, but ultimately wrong direction.

- Graders are still time intensive: first you have to make sure your grader grades correctly, then make sure its grading "works" and improves the model's performance.

Even if you use a grader, you will need to tune your model and tune your documentation, since your task is too custom for the model to ace it the first time. Next, you need to regularly check in on your model's performance and audit its results, or it will "drift" towards worse performance over time.

Why do you need all of these evals? Think of the model like a man living with a woman for the first time. He thought he knew how to do the dishes—until she told him they were in the completely wrong places. The man learns over time, with painful memories of his mistakes. This can take years… and some never learn.

Tasks, even simple ones like the dishes, have a long tail of details you need to know to succeed, and these details are not written down.

Is there a shortcut? Not in the traditional sense. Good computer use capabilities and better model "memory" will speed this process up, and we could skip a few steps here if the models became smart enough to be full time employees—or someone invents a new model architecture. Employee-caliber models seem hard to build without first going through this evaluation process on many challenging, high variance tasks.[5]